JD Vance and the Foreign Policy Election

Trump's VP Pick and the Future of Republican Foreign Policy

The Trump campaign’s Veep pick is an isolationist, a warmonger, and Ukraine-hater—or at least that’s what the coverage of his nomination suggests. The pick, as Politico put it, “doused political kerosene on the raging Republican fire over foreign policy” and “strengthened the hand of the isolationist forces eager to undo the hawkish GOP consensus that has endured since the Reagan era.”

Ok. As is so often the case with candidates’ foreign policy leanings, the media assessment of Vance’s foreign policy has been riddled with misunderstandings about the basic contours of foreign policy debate and saddled with a heavy status-quo bias that paints even the most moderate shifts in U.S. policy as extreme.

The bottom line on Vance’s nomination is much simpler: it highlights the growing influence of the realist, nationalist wing of the Republican party on foreign policy. Their approach is characterized by a willingness to reject Bush-era neoconservatism, prioritization of the China challenge, and a focus on issues like the defense industrial base, trade, and migration, rather than global alliances and value-driven foreign policy.

This is certainly not a dovish approach, nor is it isolationist. Where it is radical is not on traditional national security concerns, but rather on adjacent issues like trade and migration. And though Trump’s choice to elevate Vance is suggestive of the future direction of the party on foreign policy, it’s by no means the inevitable future of a GOP that still includes more than a few John Bolton-style hawks.

The Isolationist Canard

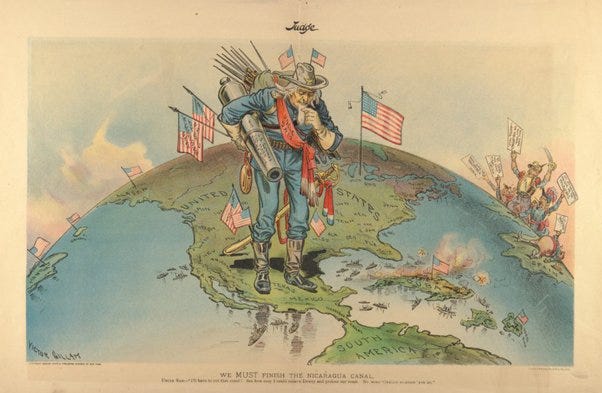

As my friend Stephen Wertheim has written—indeed, he’s written an entire book about it! – “isolationism is not, and has never been, a real position” in U.S. policy discussions. Stephen’s book traces the history of the interwar years and highlights how the term ‘isolationism’ was born primarily as a slogan against those who opposed U.S. military intervention in World War II, none of whom were calling for the U.S. to retreat from the world entirely.

This trend continued throughout the Cold War and even into the post-Cold War period, with ever-more absurd examples. The great Walter Lippmann, for example, was described as an isolationist in the press due to his opposition to the Vietnam War. Lippmann responded to critics by arguing that indeed he was isolationist, “if the limitation of our power is isolationism.” The term was later used in the context of debates over NATO expansion in the 2000s, when congressional hearings on the topic saw speculation that a mere failure to expand NATO would be isolationist.

Lippman’s quote is particularly telling: to be called an isolationist is often simply the result of suggesting that America is not omnipotent, or of arguing against a prevailing hawkish consensus. Brandan Buck over on Twitter points us to a similar quote attributed to William Howard Taft: “an ‘isolationist’ is “anyone who has opposed the policy of the moment.” And indeed, Barack Obama was once described as “an isolationist with drones” for suggesting that U.S. policy should be more cautious; Donald Trump was labeled an isolationist in 2016 for suggesting that the U.S. had wasted blood and treasure during the Global War on Terror.

Isolationism, then, is almost entirely useless as an analytical category. It tells you absolutely nothing about the critiqued person’s foreign policy -- except that the speaker dislikes it.

Vance and the Realist Hawks

Much of the criticism of Vance can be summed up by Taft’s aphorism about the current moment. Washington’s central focus for the last two years has been the war in Ukraine. There are plenty of good reasons for that: it’s the first significant land war in Europe in decades, it bears on the security of America’s NATO allies, etc. But the war itself – and the debate over its future – have become bogged down, thanks to overly optimistic predictions of Ukrainian success and falling Western public support. Ukraine’s current strategy is entirely unrealistic; no one in power is offering a coherent strategy for how to fix that.

Vance, in contrast, has been a clear voice arguing that we need to dial down U.S. contributions to the war in Ukraine and find a manageable solution. He makes the same arguments as many realists: we have reached the point of diminishing returns in this conflict, and there are significant resource constraints that will make it difficult to continue this level of support, particularly if other global crises arise.

The senator even went to the Munich Security Conference this year, and told shocked delegates that this was the way American public opinion and politics was trending. The shocked and horrified responses to his relatively banal statements suggested a lot more about the bubble-like nature of invites to Munich than it did about the actual extremism of Vance’s views. The same is true of his views on European security more broadly, where he has advocated for increased burden-sharing.

Neither view is popular in a Ukraine-obsessed Washington.

Vance’s actual language from Munich is moderate: “I offer this in the spirit of friendship, not in the spirit of criticism, because, no, I don’t think that we should pull out of NATO, and no, I don’t think that we should abandon Europe. But yes, I think that we should pivot.” That's not the language of someone who hates Europe. That's the language of a growing pool of Republican foreign policy hands who, in line with long-running realist critiques, are beginning to argue that the United States must prioritize and burden-shift to European states.

I may be just a cranky old lady at this point, but the matching of means and ends was considered an essential part of strategy when I was learning about it. It was not some radical innovation that should be distrusted. If the United States doesn’t have the stockpiles of ammunition or the defense industrial capacity to manage several global conflicts at once, then we either need to make the extremely unpopular case to massively dial up defense spending – or we need to prioritize. Means and ends that are completely out-of-whack will not achieve good results.

Yet the media discourse treats this as a strange aberration. One article even described this approach as “Asia First isolationism,” which is a tautology, a bad slogan, and a crime against the English language, all at the same time.

If we step back from Europe, moreover, Vance starts to look much more like the rest of his party. Like other Republicans – and indeed, like most of the Democratic Party these days – he’s a hawk on China. He’s hawkish on Iran and supportive of Israel. And he’s suggested that the U.S. military should be able to target drug cartels inside Mexico, an idea that’s become increasingly popular among Republicans concerned about the intersection of migration, drugs, and cartels inside Mexico.

In the case of China and Iran, certainly, it’s not at all clear that Vance is looking for a war; he’s opposed strikes on Iran in the past. But none of his rhetoric is particularly dovish, either; it only appears so in comparison to the Republican foreign policy approach of the last two decades. Vance is a dove on Iran if you compare him to Dick Cheney or John Bolton; that just means he has some common sense. This is in practice the main reason why the media’s status-quo bias is so problematic. If your baseline for foreign policy is 2007- at the peak of the war on terror - then almost anything looks like retrenchment in comparison.

Perhaps the most notable thing about JD Vance’s foreign policy background is his own relationship to those wars. He’s the first post-9/11 veteran of the war on terror to run on a major party presidential ticket; his criticisms of U.S. foreign policy orthodoxy are part of a broader trend among veterans in congress and activist groups over the last few years, particularly on the Republican side of the aisle.

What does all this mean for Republican foreign policy?

In 2016, Donald Trump’s chosen running mate was Mike Pence, a candidate who was expected to shore up Trump’s support among evangelicals, but who also didn’t align with him on foreign policy. Pence was a died-in-the-wool neoconservative, who during his tenure in congress once voted against George W Bush for trying to withdraw some troops from Iraq. And without getting into the many disturbing reasons why Pence is no longer on the presidential ticket, it's notable that this time around Trump feels he has consolidated the Republican Party enough to pick someone who broadly appears to align with him on foreign policy.

Trump’s nomination of JD Vance will probably widen the intra-Republican gap on foreign policy. Indeed, foreign policy has been a significant cleavage in the party since Trump descended his golden escalator back in 2016. A central reason why the Never Trump faction of the Republican party was so opposed to his candidacy was his perceived foreign policy stances. The first Trump administration may have been erratic on foreign policy, but the ‘Trump shock’ of 2016 nonetheless prompted significant intra-Republican foreign policy debate.

There have been several attempts to categorize these debates. Jeremy Shapiro and Majda Ruge over at the European Council on Foreign Relations, for example, have built a topology of three different camps within the Republican party: ‘restrainers,’ ‘prioritizers,’ and ‘primacists.’ My debate companion over at Foreign Policy, Matthew Kroenig, wrote a book in which he argues in contrast that there are no significant differences, and that Republicans are mostly unifying around a “Trump-Reagan” synthesis.

In my own forthcoming book on U.S. foreign policy,1 however, I argue that Republicans are increasingly clustering around two distinct worldviews: First are the neoconservative or primacy-leaning Republicans who adhere to much of the consensus of the last three decades, and who still have much in common with their political opponents in the Biden administration. They advocate an assertive and forward-leaning strategy that seeks to leverage US military and financial power – sometimes for liberal ends, sometimes unilaterally – but always broadly. Nikki Haley, Mike Pompeo, Liz Cheney and even Mitt Romney all belong to this group.

The second group are also often hawkish, and more than willing to use military force – or economic coercion – when they believe it is necessary. But they are much more willing to be selective about the use of U.S. force, more concerned about the rise of China than conflicts elsewhere, and much more willing to see alliances as tools to achieve U.S. national interests than “sacred obligations” of some kind. They’re also increasingly protectionist on trade and anti-immigration. Vance clearly fits within this group.

In the context of Republican foreign policy, ultimately, the fact that Vance received the VP nod and not Haley, Pompeo, or even Rubio, is likely to empower this second group further. Vance is young and potentially could be around Republican politics for a long time; this fact alone may make him more consequential than many VP picks when it comes to foreign policy.

What about the election?

Elections are not won or lost on foreign policy – or at least not in the ways that we typically think about it. Occasionally, a significant foreign policy disaster may have bearing on an electoral result – Carter and the Iran hostage crisis, or Johnson and the Vietnam War – but foreign policy typically ranks lower in salience for voters than issues like the economy.

At the same time, it's also highly unusual to see the kind of gap on foreign policy between the parties that the 2024 election promises. For much of the post-Cold War period, a bipartisan consensus existed around a form of ‘liberal hegemony.’ Presidential candidates certainly criticized one another for not being tough enough on foreign policy, but in-office, they demonstrated few policy differences.

A Trump-Biden rematch will almost inevitably involve more foreign policy debate than other elections; Biden has made his foreign policy legacy a centerpiece of his campaign. Indeed, his own case and his advisors’ case for keeping him as the Democratic candidate often leans on his foreign policy achievements.2 The erratic nature of foreign policy during the first Trump administration also leaves plenty of opportunity for Biden and Democrats to attack Trump on the issue.

But in ideological terms, the two candidates are worlds apart on foreign policy. Biden is perhaps the foremost proponent of the foreign policy status quo; since 2016, meanwhile, Trump's America First rhetoric has advanced from fringe to a mainstream foreign policy view. It's entirely possible that other issues, from abortion to social spending, will end up dominating the election. And given Trump's worrying record in almost every area related to the rule of law, you could make a solid argument that voters shouldn't be voting on foreign policy.

But foreign policy remains a notable policy contrast between the two men, and one which plays in Trump’s favor. All we have to do is to picture the contrast: a declining, greying Biden telling voters that American power can do everything, in a world where clearly not everything is going well, compared a braggadocious Trump saying ‘we should put America first’ and ‘we should ask other countries to pay their own fair share’?

That’s a bad comparison for Biden.

Spoiler! First Among Equals: U.S. Foreign Policy for a Multipolar World is coming in 2025.

I’m going to assume a Biden-Trump rematch unless something actually changes. A Kamala Harris-Donald Trump match up or Shapiro or Whitmer or any of the others might lean less on foreign policy, but it would still present a difference between the parties. We also know surprisingly little about how any of the Democratic replacements for Biden might pursue foreign policy — that’s a question for another day.

The problem is that Trump is weak, stupid and easily manipulated.

It's not an easy thing to maintain hegemony over the world economy.

Why wouldn't U.S. capitalism choose the most aggressive, rapacious and ruthless representatives.

FYI:

"... It goes without saying that in our opinion the inevitability of a crisis is entirely beyond doubt; nor, considering the present world scope of American capitalism, do we think it is out of the question that the very next crisis will attain extremely great depth and sharpness. But there is no justification whatsoever for the attempt to conclude from this that the hegemony of North America will be restricted or weakened. Such a conclusion can lead only to the grossest strategical errors.

Just the contrary is the case. In the period of crisis the hegemony of the United States will operate more completely, more openly, and more ruthlessly than in the period of boom. The United States will seek to overcome and extricate herself from her difficulties and maladies primarily at the expense of Europe, regardless of whether this occurs in Asia, Canada, South America, Australia, or Europe itself, or whether this takes place peacefully or through war."

Leon Trotsky, 1928

https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1928/3rd/ti01.htm